What if you could grab a healthy breakfast and mail a package during your morning commute, buy a birthday gift or book midday, pick up dry cleaning on your way home in the evening, and shop for a new spring wardrobe during a weekend outing—all in one central location?

The concept is increasingly becoming a reality—or at least, a goal—for transit-oriented development hubs (TODs) around the globe.

The best examples are those in which the transit station is both a desirable destination and a centerpiece of the community where people meet, eat, celebrate, play, and, most importantly, shop.

According to a recent retail report released by CBRE, one-fifth of brands from the Americas and EMEA are targeting travel hubs (such as airport and railway terminals) as an emerging format for expansion.

The Oculus structure acts as the main hall for the World Trade Center Transportation Hub in NYC.

New York City’s World Trade Center Transportation Hub includes the Santiago Calatrava-designed main hall, the Oculus, which opened to the public earlier this month. Twelve years and $4.4 billion in the making, the hub is still in a partially completed state—including a retail section still under construction—but once fully realized, could become a core hub for Lower Manhattan.

“These kinds of place-oriented TODs can support an array of retail activities, across the spectrum of restaurants, consumer goods, boutiques, household services and professional services,” says Robert Cervero, professor and chair of city and regional planning at the University of California, Berkeley.

“This is very much the Scandinavian model of TOD, where the transit station is not just a logistical node but also a place to go, in and of itself.”

As more people move from car-dependent locations to areas with bustling transit hubs, the consolidation of trips—in other words, one-stop shopping—becomes a sought-after lifestyle factor.

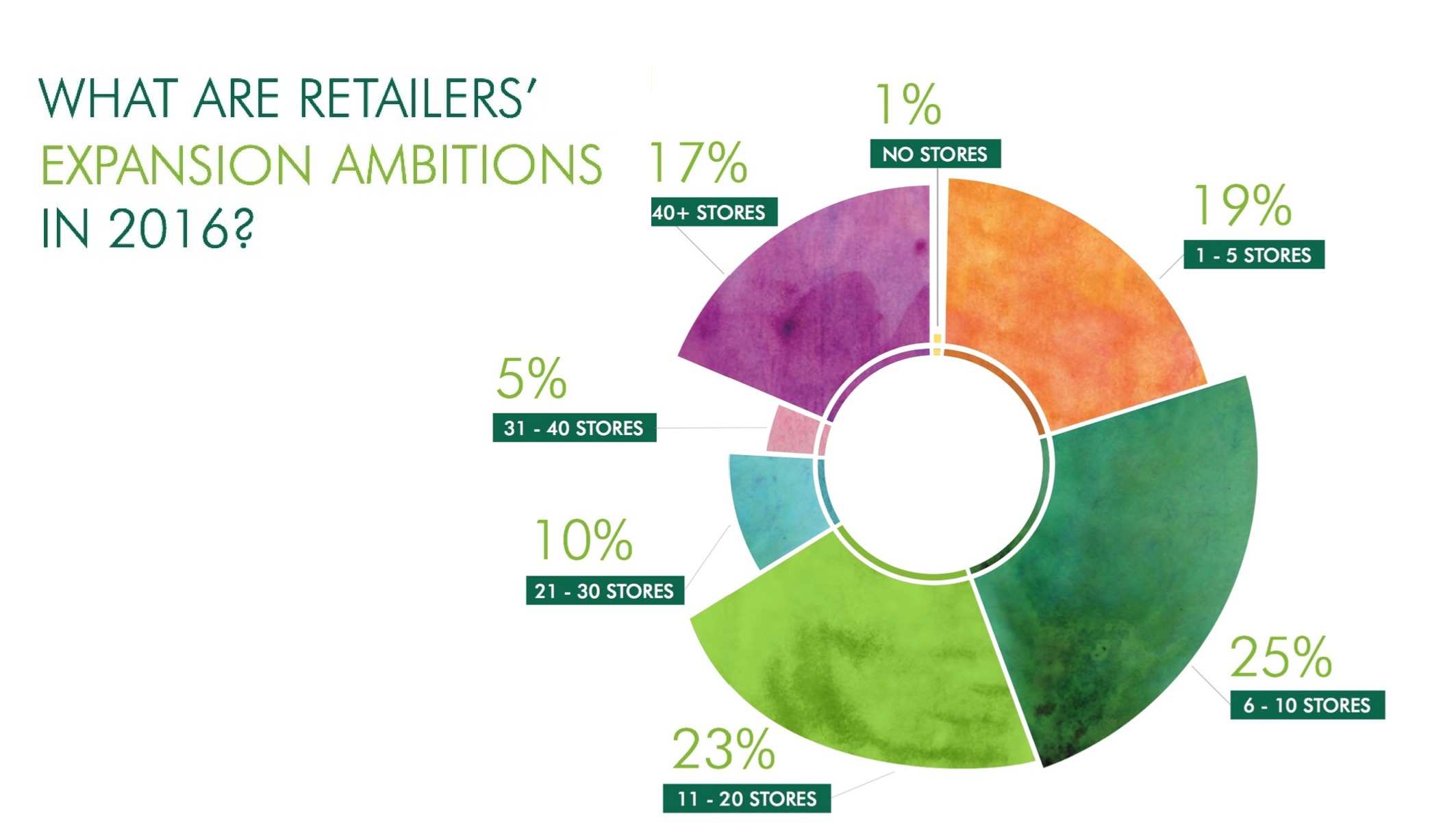

Source: CBRE Research, 2016

A SPACE ISSUE

“Cautiously optimistic” may be the buzzword when it comes to retail expansion in 2016: According to the CBRE report, approximately two-thirds of retailers surveyed are looking to open no more than 20 stores this year, and name lack of quality space as a significant factor.

Thus, the square footage offered by emerging TODs presents an attractive option. Particularly when integrated into a neighborhood where locals are working, attending school and participating in community services, quality retail within TODs feels like a natural extension of the local ethos.

“Retailers are consolidating near rail stations to allow efficient interconnection of activities,” Cervero notes. However, he adds, “There must be other activities generating traffic in the non-commute periods.”

Transit users alone are often too slim of a market niche to support and sustain retail. Since serving existing communities and fostering future growth are also important factors, the goal is to develop mixed-use TODs that attract visitors not only during the morning and evening rush hours, but also during the weekday, at night and on weekends.

In many instances, successful retail-oriented transit hubs have grown out of the collaboration of both transit and retail, as evidenced by global cities with busy metrorail systems and successful retail such as Raffles Place in Singapore, Covent Garden in London and Shinjuku in Tokyo.

“In general, these have been less the product of master-planned TODs or transit hubs to include retail but rather co-development—public (transit agency) and private (retailers) jointly planning their improvements in tandem with or in recognition of each other,” Cervero states.

It’s a tandem strategy for retailers and developers alike.